Love him or hate him, you can’t deny that President Donald Trump has a unique way of doing things – and that his methods are often chaotic. But to paraphrase William Shakespeare, there is method to Trump’s apparent madness. And, it must be said, chaos isn’t a bad thing…

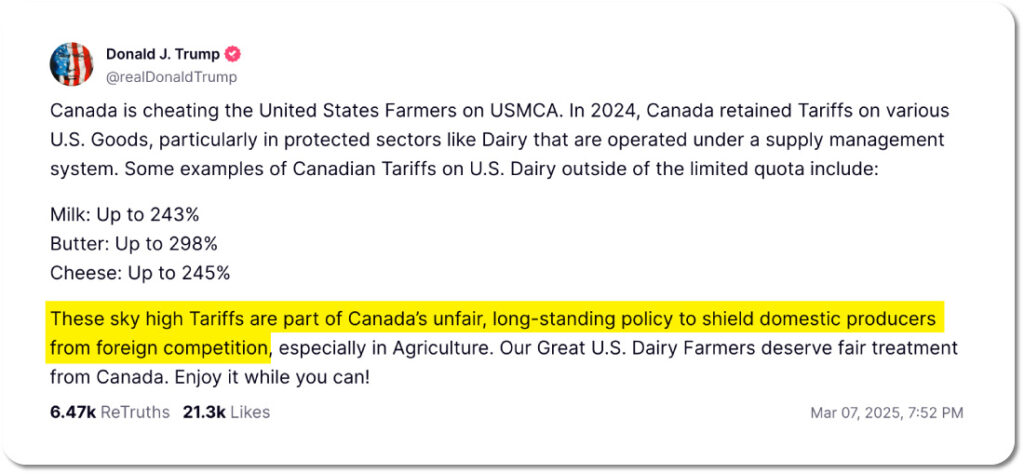

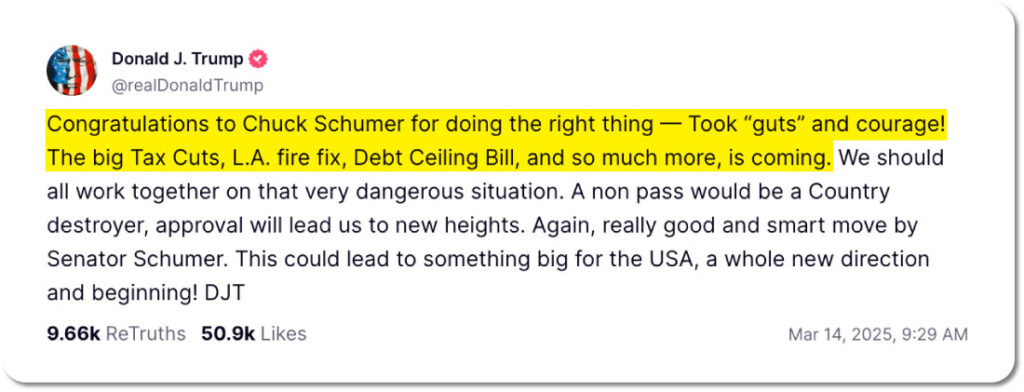

I’m mostly talking about Trump’s Twitter account. He was banned from the app after leaving office in 2021, but after Elon Musk bought Twitter a few years ago and rebranded it to X, he let Trump back on the platform after polling users, where the majority voted to reinstate Trump. Musk tweeted, “The people have spoken. Trump will be reinstated. Vox Populi, Vox Dei.” Translated, the Latin phrase means “The voice of the people is the voice of God.”

The president wasted no time in resuming his antics, and now a single tweet from the White House can change the direction of a stock, an index, or even the entire market. Nobody knows when Trump will tweet. Nobody knows exactly what he’ll say, either, maybe not even Trump himself. It’s chaotic…

But chaos provides opportunity. Too much stability is no different from stagnation, and just as a forest fire clears away dead trees and debris and allows for new trees to grow, chaos in the markets destroys companies just coasting along and launches ones with ambition and vision into the stratosphere.

And we can identify the best opportunities with the S.I.P. strategy. S.I.P. stands for Scan, Identify, Play. It’s how I pick the stocks we’re trading on. I won’t get too into the weeds, but I have a program that scans the market to find potential opportunities. I then use a set of proprietary criteria to evaluate each one and identify the best. Finally, we play the best of those opportunities.

In these Trump catalyst trades, we will be using one asset and three plays uniquely well suited to playing all of Trump’s tweets. As catalyst traders, we love sharp, fast moves, so let’s get started with what exactly we’ll be trading: options.

Your Best Option

Let’s start with the basics. What is an option?

In short, an option is a contract. It gives its holder the right – but not the obligation – to buy or sell 100 shares of stock on a designated date. You can learn more about options in my other report here, but for now I will give you a quick primer…

Every option is linked to a specific stock, index, or futures contract. So whenever you place an options trade, its price will be affected by the movement of its underlying asset.

There are two types of options: calls and puts.

A call option gives you the right – but not the obligation – to buy 100 shares of a particular underlying stock at a specific price (the strike price) before a specified date in the future (the expiration date).

The opposite of a call is a put. A put option conveys the right – but again, not the obligation – to sell 100 shares of a stock at the strike price by the time the put option expires.

All options have expiration dates, which typically land on Fridays.

Here’s how they work.

You could buy 500 shares in Company XYZ, which is currently trading for $10 a share.

Excluding commissions (which are increasingly becoming a thing of the past), that will cost you $5,000. However, you may not want to spend $5,000 on the trade.

So rather than buy the stock outright, you can buy options on it – which are significantly cheaper per share. If you bought five call options, that would give you the right to buy those same 500 shares at a certain price by a certain time (5 call options x 100 shares per option = control over 500 shares). And those call options might be just $1 each, or $100 per contract ($1 per share x 100 shares per contract = $100 per option). So, you’d spend $500 to control 500 shares instead of $5,000 to buy the stock outright.

If the stock goes up, the option price should increase as well. Though not by the same amount. There are a variety of factors that influence this, including how much time is left until expiration and how volatile the stock is.

But owning a call option is a way to take advantage of a stock going up without having to buy all of those shares. You can do it for much less.

Similarly, if you think a stock is headed lower, you can buy puts rather than shorting the shares.

Next, you need to pick a time frame for your scenario to play out – the end of which is known as the expiration date. This can be anything from days to years out.

Options prices vary depending on the option’s expiration date, its strike price, and the volatility of the underlying stock or index. But I won’t get into that here.

Once you’ve done all that, you’re ready to buy.

When you buy an option, it is as though someone is saying, “I will allow you to buy or sell 100 shares of this company’s stock at a specified price per share at any time between now and the expiration date.”

And it’s further understood that for this right, they expect you to pay a fee.

That fee is called the premium, which will vary considerably depending on the exercise price and time until expiration as well as the stock’s volatility.

Alternatively, if you are selling (writing) the options, you collect the premium. I’ll have more on how we use that to our advantage later.

Now you have an idea of what options are, but there’s one more step you need to take to actually trade them…

Approved!

To trade options, you will need your broker’s approval. But don’t worry. It’s not hard to get approved. To do all the strategies listed in this report, you’ll need what’s called Level 3 approval, so be sure to ask your broker for Level 3 approval. (Note: Charles Schwab starts its options trading account levels at zero, so for that broker it’s Level 2.)

No matter what broker you use, the process to get approval usually begins with simply filling out a form on your broker’s website.

When you do, make sure you indicate you have some experience. If you have none, no worries. You can paper trade for two weeks to gain experience. (See our guide here on how to get started.) Even paper trading counts when you go to get option level approval. You’ll also want to select speculation or growth as part of your investment objectives.

The broker will want to know that you’re comfortable taking on some risk, so be sure to choose moderate or high risk tolerance. We won’t be making high-risk trades, but your broker wants to know you can handle it should you choose to do so.

You may also have to disclose income or liquid net worth (though you usually won’t have to provide any proof).

If you are asked why you want Level 3 approval, explain that it’s so you can trade debit spreads and strangles (more on those momentarily).

Follow these steps and you should be approved very quickly. Do not hesitate to reach out to your broker specifically if you have any questions on how it does options approval. Now on to the fun part…

Spread the Wealth

Two of the three types of trades we will be doing in this service are very similar to one another. Both are “debit spreads.” A debit spread is made when you simultaneously buy and sell two options of the same class (either both puts or both calls) with the same expiration date, but with different strike prices.

A debit spread comes in two varieties: a bull call spread and a bear put spread. More on each of those in a moment.

The sale of the one option offsets the cost of buying the other, but it will cost you to establish one. A debit spread limits both your potential return and your potential loss, but it also cuts risk considerably and you can exit the spread early, changing it into an ordinary long call or long put.

I know that might sound a little confusing at first, but my examples should clear it up…

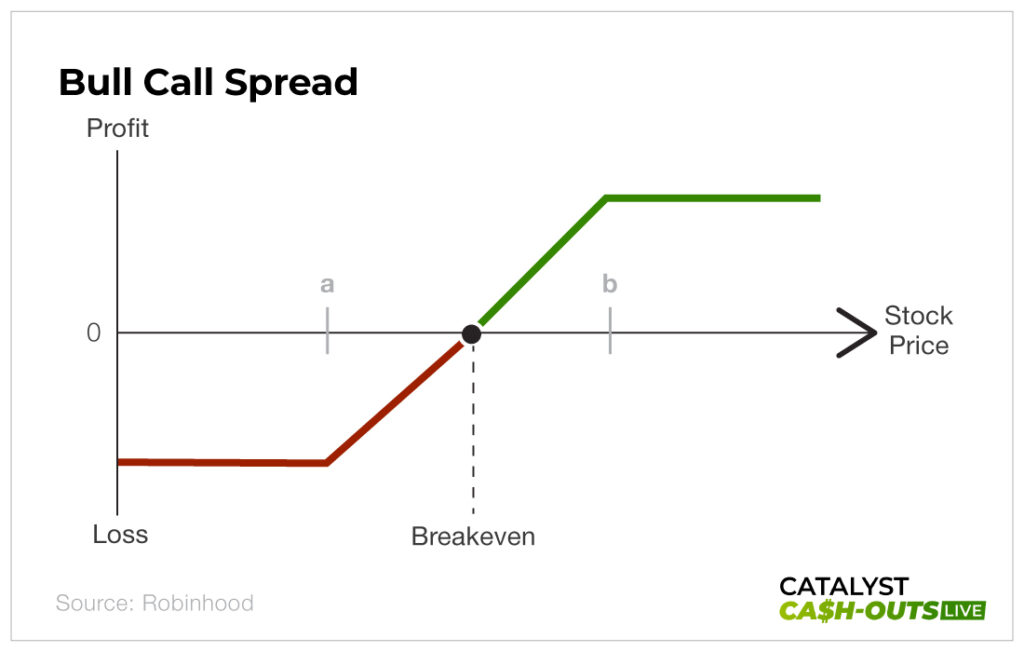

Play No. 1: Bull Call Spread

Let’s start with the bull call spread. Say we think Company X, which is trading at $100 right now, will move up in the near future but we don’t want to risk a long call position on it. So we choose to set up a bull spread.

We do that by simultaneously buying a $105 call and selling (writing) a $110 call on Company X, each with the same expiration date.

For the sake of this example, let’s say the $105 call costs $3, or $300 per option, and we buy 10 of them for a total cost of $3,000. That’s our long call. We also sell the same number of $110 calls for $1, or $100 per contract. For 10 contracts we make $1,000 selling those calls. That’s our short call. The main purpose of short calls is to help pay for long calls’ upfront costs.

That means our net debit for this trade is $2 per share, or $2,000 total between the cost of buying the 10 $105 calls for $3,000 and the income from selling the 10 $110 calls for $1,000. The $2,000 is also the maximum risk until expiration. It’s the most we could lose should the trade go against us.

Now, we have successfully set up a $105-$110 bull call spread on Company X, so at what point do we make money? For that, we need to figure out our break-even point. For a bull call spread, that’s the total cost of the spread ($2 per share) plus the strike price of the option we bought ($105), or $107 total. That means we will make money if the underlying share price of Company X exceeds $107 at expiration.

That’s lower than the $108 break-even point we would have had if we’d simply bought the $105 call ($3 per share cost + $105 strike price = $108 breakeven). So we have spent $1,000 less setting up the trade and limited our risk considerably while positioning ourselves for profits.

Now let’s take a look at how our bull call spread might play out.

The absolute worst-case scenario is that we’re wrong and the trade goes against us – Company X drops to $95 and all our options expire worthless. In that case, we lose the $2,000 we spent setting up the trade and not a cent more. Limited risk.

If Company X hits our break-even point of $107, then we will make $2,000 from the long call and cancel out the cost of setting up the trade. We won’t have made any money, but we won’t have lost any either.

Now, let’s say we’re totally right and Company X surges to $111. In that case, our long call ($105) is worth $6 while our short option ($110) is worth $1. The total value of our spread is now $6 – $1, or $5. Subtract the cost of the spread ($2) to get our profit, which is $3 per share, $300 per option, $3,000 for the whole trade.

That’s a $3,000 gain on a $2,000 investment, or a 50% win with low risk. Not a bad deal. But our play doesn’t need to end there.

Our spread’s profit is maxed out at $5 because of the calls we sold to lower our risk. Now, we can buy back those $110 calls if we think Company X will surge even higher. That’s a riskier move, as our spread becomes a simple long call play, but it could make us a lot more money.

Alternatively, you could set a wider window on the spread, say, selling $115 or $120 calls. But the further out of the money you go, the less those calls will sell for and the more the trade will cost you to set up.

That’s the bull call spread, but what if we think Company X is going down? In that case, we set up a bear put spread.

Play No. 2: Bear Put Spread

We do that in a very similar way to the call spread we just set up. For the sake of easy math, let’s say Company X is still trading at $100. To set up a bear put spread, we would buy $95 puts for, let’s say $3 per share (our long puts), while selling $90 puts at $1 per share (our short puts). Say we buy 10 puts for $3,000 while selling 10 more for $1,000. That gives us the same $2,000 debit, or cost, to establish the trade.

We’ve now set up the $90-$95 bear put spread on Company X. As with the bull spread, our maximum loss is $2,000 and our maximum gain is the width of our spread ($95 – $90 = $5) minus the $2 per share cost, so it’s $3 per share in total, or $3,000 for the whole trade.

Our break-even point works similarly to how it did for the bull spread, only we’re subtracting the $2 per share cost from the $95 long put, which gives us a break-even point of $93 ($95 – $2 = $93). That means Company X needs to drop to at least $93 for us to break even – anything below that is profit. If we had just bought the puts, our break-even point would be $92.

Once again, let’s start with the worst-case scenario. Say we’re wrong and Company X leaps to $105. In that case, all of our puts will expire worthless and we’ll have lost the $2,000 we spent. We would be out $3,000 if we hadn’t set up the spread.

Say Company X drops to our break-even point of $93. In that case, we make $2,000 on our $95 puts while the $90 puts expire worthless. The $2,000 profit cancels out the $2,000 we spent to set up the trade, and we don’t lose anything, but we also don’t win anything.

Now, say we were totally right and Company X drops to $89. In that case, our $95 puts are worth $6 and the $90 puts we sold are worth $1. The total value of our spread is $5 per share. When we exit, we subtract the $2,000 we spent setting up the trade for a total profit of $3,000, another 50% gain.

As is the case for its bull counterpart, if it looks like Company X is going for a full-blown nosedive, we can buy back our short $90 puts and let our $95 puts ride as a normal long put play. Once again, this adds risk but raises our potential reward considerably.

So now we’re covered whether Trump’s tweets cause a spike or a dip. But what if we have no clue how the president’s tweets will impact the market? Fortunately for us, there’s also a win-both-ways trade…

Play No. 3: Stranglehold

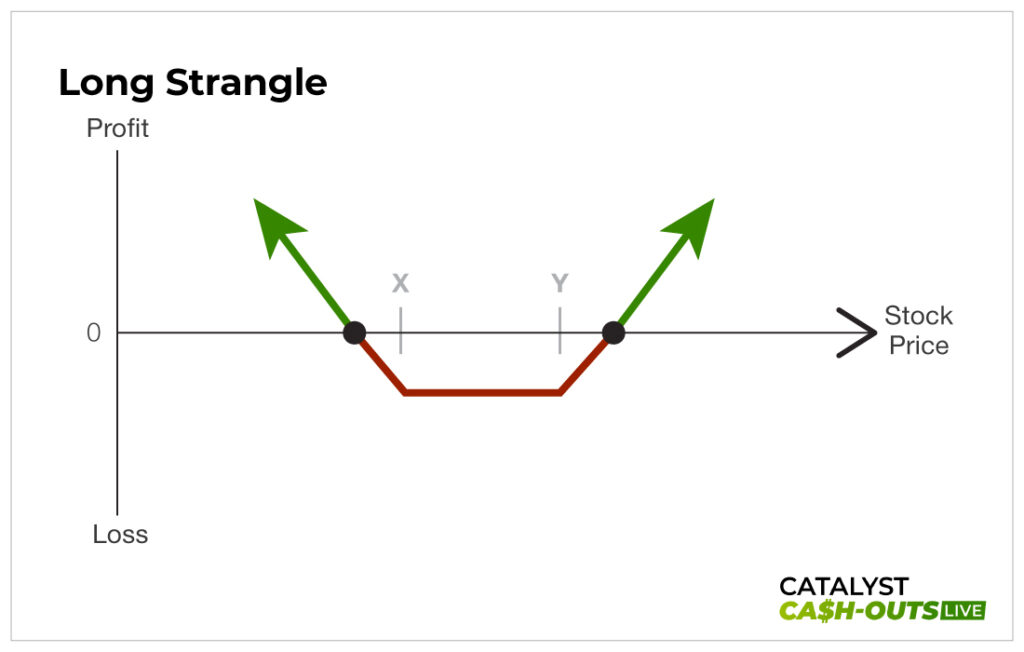

Now, there’s no such thing as a sure thing in the stock market. There is always some amount of risk, even with the safest assets. But the closest you can get is likely a strangle.

To set up a strangle, you buy an out-of-the-money call and an out-of-the-money put with the same expiration date, near the current trading price of the asset you’re making the play on. The unknown Trump tweets are likely our best opportunity for these because, while debit spreads limit your risk, they come at the cost of capping your profits. With a strangle, your losses are limited to the cost of setting up the trade while your profit potential is theoretically unlimited. However, setting up a strangle is more expensive, so we will be using this strategy when we expect more dramatic moves, as our break-even points either way will be further away.

Allow me to illustrate…

Let’s bring back Company X one more time, still trading at $100. Say Trump tweets about it one night and we know his words are going to have an effect; we just have no earthly idea whether they’ll be good for Company X or bad for it.

So, we set up a strangle. We do that by buying 10 $105 calls at $3 and 10 $95 puts also at $3. We’re positioned on either side of Company X’s $100 trading price, so we’re set no matter which way it goes. However, our cost for this trade is $3,000 for the 10 $105 calls and $3,000 for the 10 $95 puts, so we’re in for $6 per share, or $6,000 total on this trade.

Our upside breakeven is our call strike price ($105) plus the per-share cost of the puts and the calls ($6) for a breakeven of $111. Our downside breakeven is the $95 strike of our puts minus the $6 per share cost of our options, or $89. That means to make a profit we need Company X to go either above $111 or below $89.

While our total outlay is higher than a debit spread’s would be, our risk is still limited here to the amount we paid: $6,000. That means if Company X doesn’t move much, then we lose the trade but our losses are still capped. We know how bad it could be if the trade goes against us, so there aren’t any surprises waiting for us.

So what could happen?

Say Company X surges to $115. In that case, our puts expire worthless and our calls are worth $10 per share ($115 share price – $105 strike price = $10), or $10,000 for the lot of them (10 contracts with 100 shares each x $10). Subtract the $6,000 we paid to set up the strangle from that $10,000 for a tidy $4,000 profit.

If it went the other way and Company X dropped to, say $85, our calls would expire worthless and our puts would be worth $10 per share (strike price of $95 – share price of $85 = $10, or $10,000 for the whole lot of 10 options), so we would take home a $4,000 profit ($10,000 from the puts minus the $6,000 cost of setting up the trade).

Note that options pricing and valuation are more complicated than in these examples. There’s also time value to consider, among other things. But I am using easy numbers and math to illustrate how these spreads and strangles work from a purely mechanical standpoint. It will never be this clean in the markets, but it can be just as profitable, if not more so…

Tweets You Can Take to the Bank

Armed with the three trading strategies in this report, we’re set to profit from the outcome of the chaos created in the markets by Trump’s tweets whether they send stocks up or down. Be on the lookout for new trade setups in your inbox, and check out the livestreams here for the latest updates…

Regular options plays are all well and good, but debit spreads and strangles give us far more protection if the market goes against us while still allowing us to take home some serious gains. And it’s all thanks to the commander in chief’s social media habits.

For most people, Twitter is a diversion or a spot for endless doomscrolling. But with Trump back in the White House, tweeting up a storm, it can be a source of income too. Forget scrolling for a funny video or a hot take someone thought was worth 280 characters…

These are tweets you can take to the bank.